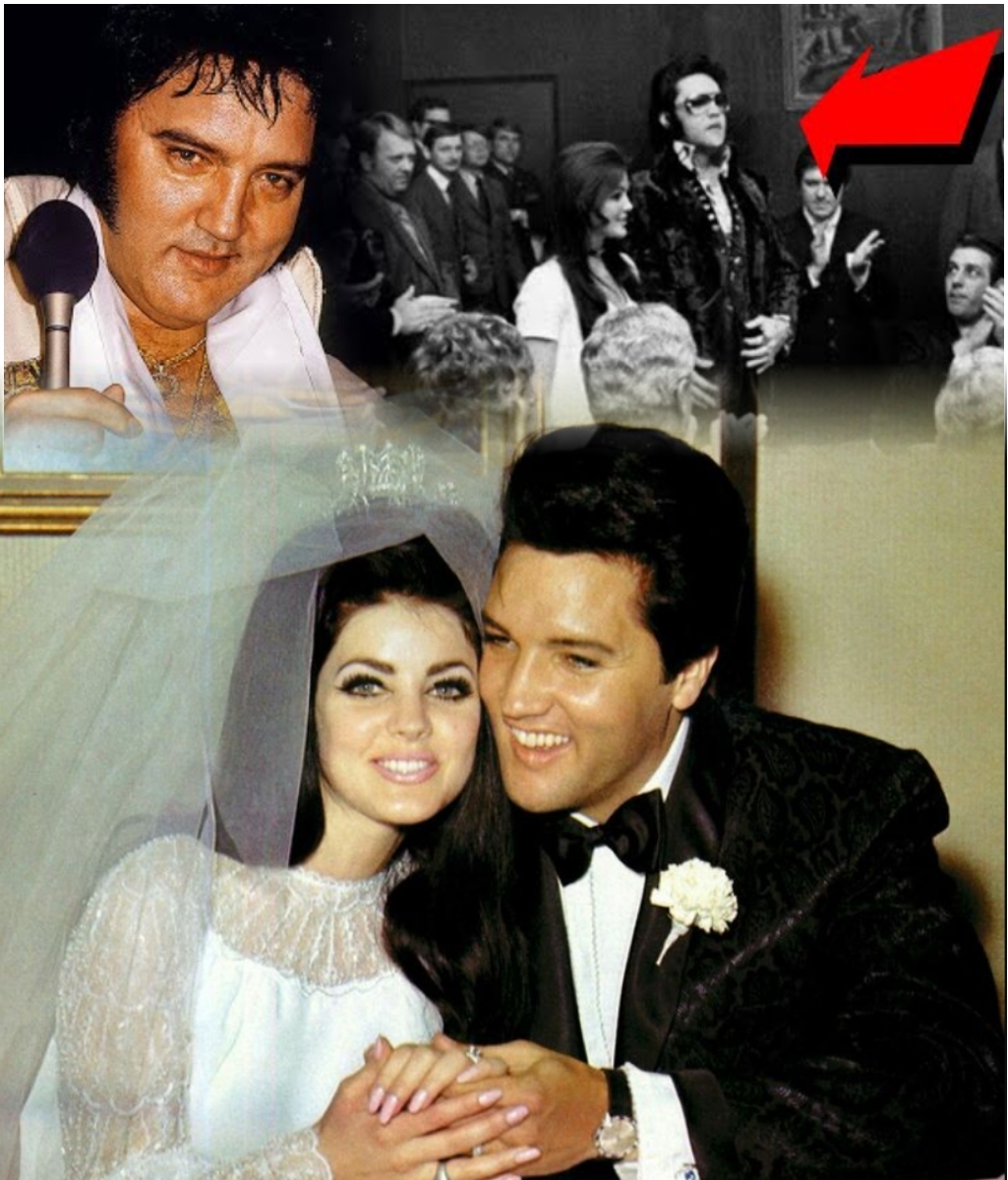

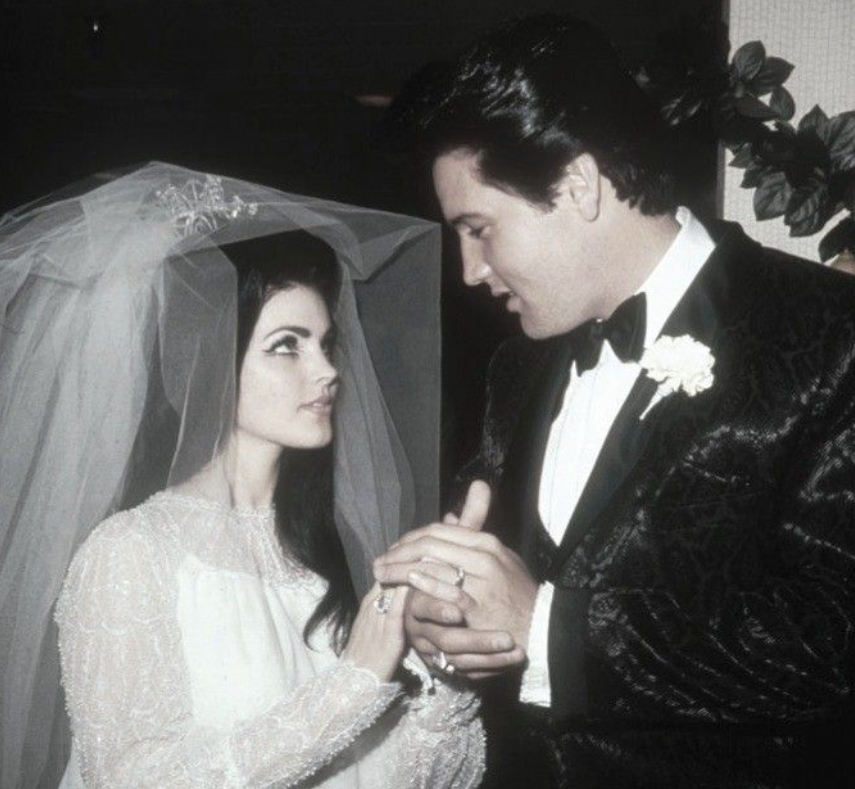

When the marriage of Elvis Presley and Priscilla Beaulieu Presley ended in 1973, the world was stunned. The union had begun like a fairy tale — the King of Rock & Roll and the young woman who had shared his life at Graceland — but by the early seventies, the pressures of fame, distance, and temptation had fractured the bond. For decades, speculation has swirled around the details of their split, and Elvis himself often fueled the fire by offering versions of the story that didn’t quite match the truth.

In interviews following the divorce, Elvis would sometimes cast himself in a sympathetic light, suggesting that it was Priscilla who had grown restless, that she had changed while he was away on tour, and that she had been the one to step away first. At other times, he insisted that the breakup had been amicable, a natural conclusion to a love that could not withstand the relentless demands of his career. But those who were close to both of them knew that these accounts were only part of the picture — and in some cases, far from accurate.

Friends recall Elvis telling stories that painted Priscilla as distant, even unfaithful, claims which she has repeatedly denied. In truth, Priscilla had long endured Elvis’s own infidelities and long absences, and her decision to leave was born out of years of strain. Yet Elvis, ever conscious of his public image, often shifted the narrative to protect himself from being seen as the one at fault. “He never liked to admit weakness,” one insider later remarked. “Even when it came to love, Elvis wanted to believe he was in control.”

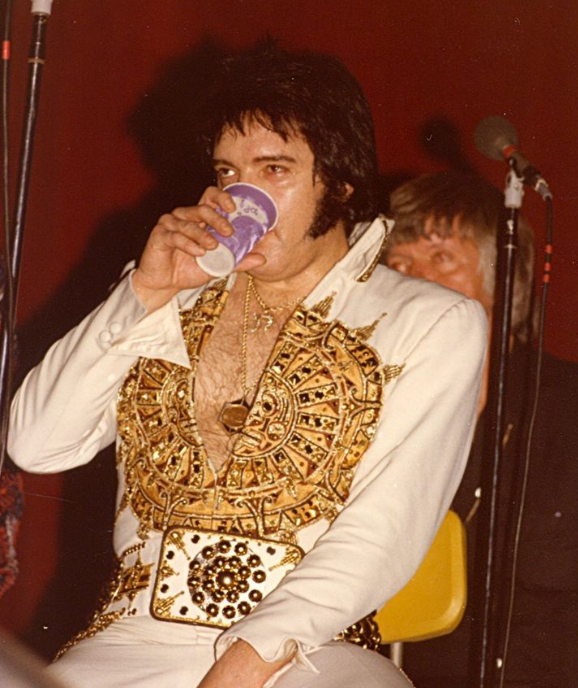

What makes these contradictions so fascinating is how they reveal the tension between the public Elvis and the private man. Onstage, he sang songs of heartbreak with searing honesty — ballads like “Always on My Mind” that seemed to hint at regret and longing. But offstage, his words about Priscilla often bent the truth, shaped less by honesty and more by the need to manage the myth of Elvis Presley.

Priscilla herself has since spoken candidly about the divorce, describing it as painful but necessary, and admitting that their relationship had been far from the picture-perfect romance fans imagined. Her accounts often stand in direct contrast to Elvis’s shifting narratives, leaving fans to sort through the contradictions and decide what to believe.

The tragedy is that beneath the exaggerations and denials was a simple truth: Elvis and Priscilla had loved one another deeply, but the weight of fame, constant separations, and the pressures of his lifestyle made it impossible for their marriage to survive. His untrue claims were less about deceit and more about a man struggling to reconcile the image of the King with the reality of being left behind.

In the end, their divorce was not about villains or betrayal, but about two people overwhelmed by circumstances larger than themselves. And yet, even in his moments of denial, Elvis’s voice betrayed the pain he carried. When he sang of love lost, of nights alone, of the haunting ache of memory, listeners heard the truth he could not fully admit in words.

It is perhaps in those songs — more than in any interview or statement — that Elvis confessed what really broke his heart.